Gates Foundation funded research face challenges to publish on top-tier journals

Researchers funded by the Gates Foundation are facing difficulties publishing on some top-tier journals. This is due to open access (OA) policy that the Gates Foundation and journal publishers follow, according to the Nature’s writer Richard Van Noorden.

The Gates Foundation in 2014 put open access policy that mandates immediate open access publishing. It also requires researchers to make their research data open. This policy came into effect starting January 2017. However, open access policies many top-tier journals such as Nature, Science, the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) and the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) have do not allow immediate open access. They impose embargo period that ranges from six months to one year depending on the type of discipline.

The Gates foundation is not considering revising its policy or exempting these journals. As a result, some research findings might not be published on these journals. To address the issue, there is ongoing discussion between journal publishers and the Gates Foundation, according to the Nature. In the past, the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) forced journals to comply with its OA policy requirements.

According to the Nature, about 2000 to 2500 articles funded by the Gates Foundation published each year. Most of them, around 92%, are published on journals that comply with what the Gates Foundation requires. That means only 8 % of them will be affected by the Gates Foundation’s OA policy that does not allow embargo imposition.

Different research funders had different open access policies. For instance, the Wellcome Trust allows publishers to impose embargo period (max one year) on research it funds. Read more

US Gov’t Takes On Predatory Publishers

By Carl Straumsheim| The Federal Trade Commission on Friday filed a complaint against the academic journal publisher OMICS Group and two of its subsidiaries, saying the publisher deceives scholars and misrepresents the editorial rigor of its journals.

The complaint, filed in the U.S. District Court for the District of Nevada, marks the first time the FTC has gone after what are often known as “predatory” publishers. Such publishers exploit open-access publishing as a way to charge steep fees to researchers who believe their work will be printed in legitimate journals, when in fact the journals may publish anyone who pays and lack even a basic peer-review process.

Ioana Rusu, a staff attorney with the FTC, said in an interview that the commission is responding to a growing number of calls from people in academe for some sort of action to be taken against publishers that take advantage of scholars wishing to publish in open-access journals.

“There was definitely a sense that nobody had done anything about it,” Rusu said. “Now we’re watching.”

OMICS’ business practices have been scrutinized for years. The company, based in Hyderabad, India, publishers more than 700 open-access journals, and has created a number of imprints — including iMedPub, also named in the complaint — to expand its presence in the scholarly publishing market. Several of OMICS’ journals have names similar to other, legitimate journals, which critics say is an attempt to confuse scholars.

“If anything is predatory, it’s that publisher,” said Jeffrey Beall, scholarly communications librarian at the University of Colorado at Denver. “It’s the worst of the worst.”

Beall is known for his lists of thousands of “predatory” journals and publishers, and he has for several years written about OMICS and other publishers on his blog. Last month, for example, he published a handful of emails sent to him by researchers caught by surprise by four-digit publication fees or struggling to withdraw their papers from OMICS journals.

Those are the kinds of practices the FTC highlighted in its complaint. OMICS, the commission alleges, does not adequately disclose that authors have to pay a publication fee, falsely claims that its journals are frequently cited and lists academic experts with no connection to the journals as editors.

“As a result, in many instances, consumers only discover that their articles will not be peer reviewed and that they owe fees ranging from several hundred to several thousands of dollars after Defendants inform them that their articles have been approved for publication. Consumers’ attempts to withdraw their articles are frequently rejected, thereby preventing them from publishing in other journals,” the complaint reads. Should the court not take action, it adds, OMICS will continue to “injure consumers, reap unjust enrichment, and harm the public interest.”

The complaint extends to OMICS’ event business, managed through the subsidiary Conference Series. According to the complaint, OMICS regularly advertises conferences featuring academic experts who were never scheduled to appear in order to attract registrants.

OMICS did not respond to a request for comment, but posted a comment to this article this morning denying all charges.

Even if the FTC is successful in its case against OMICS, the commission will only make a dent in the world of “predatory” publishing. One study by researchers at Finland’s Hanken School of Economics found that such publishers flooded the scholarly communications landscape with more than 420,000 articles in 2014, about eight times as many as in 2010.

The FTC does not intend to file thousands of complaints — nor does it have the resources to do so — but Rusu said taking action against OMICS represents the commission announcing its interest in a new field. Typically, the FTC will do so by strategically targeting “some of the most recognized and also some of the worst actors” in that space, she said.

“With a lot of our other areas in which there are bad actors, the best you can hope for is that it’s setting a precedent, … marking a line in the sand and telling people that’s not OK,” Rusu said. “We don’t care if you’re marketing debt collection or publishing.”

Rusu stressed that the FTC is not passing judgment on open-access publishing in general. “We take no sides between the traditional subscription model and the open-access model,” she said. “We believe both of them can be done in a fair, open, clear and lawful way. What we have a problem with here is people who are trying to benefit from the open-access model to scam people.”

The FTC is seeking both monetary relief for researchers that have published with OMICS and to prevent the publisher from further violations of the Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914. Read more

The Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ), a leading open access journals’ index, has decided to tighten the standards for journals’ acceptance, in order to rule out dubious and inactive publishers.

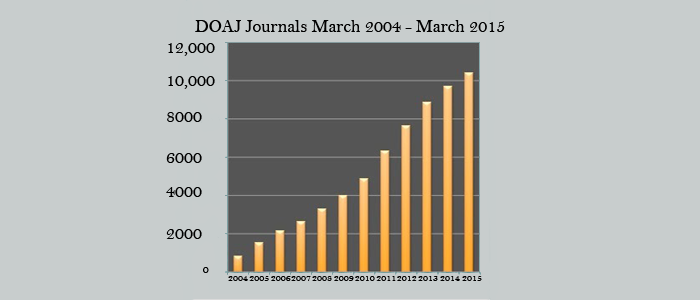

Functioning on a voluntary basis, DOAJ is a community-curated list of peer-reviewed open access journals. In the past few years, the number of journals indexed at DOAJ grew almost exponentially, (see graph) from the initial 300 journals listed in 2003, to around 11,000 journals in the beginning of 2016.

Escaping predators

However, this growing trend flipped in the last six months, after the removal of around one-third of DOAJ’s indexed journals. The DOAJ started a ‘quality-check’ process in 2014, after facing harsh criticism for listing several predatory publishers– collecting article processing fees (APCs) while offering low quality journals, mostly without undergoing (rigorous) peer review processes.

Every publisher listed at the DOAJ was asked to resubmit their journals’ applications, which were then evaluated on the basis of more strict criteria. Lars Bjørnshauge, DOAJ’s managing director, explained to the Nature journal that publishers who failed to either resubmit or to provide reliable information about their mission, location and operation were excluded from the open access directory. The list of the excluded journals can now be found at the DOAJ’s website.

Open access on the rise

According to DOAJ, the number of open access journals is on the rise; every week, around 80 open access publishers apply for indexation. Yet, a large amount of those publishers fails to meet DOAJ’s quality criteria; only in the last two years, around 5,400 applications were rejected, mainly due to the lack of information regarding licensing rights, publication permission and editorial transparency.

Lars Bjørnshauge recognizes that the major challenge in the current open access landscape is no longer finding new open access publishers, but rather to keep the existing ones under a strict quality control. After excluding 3000 dubious open access journals from its index, DOAJ now plans to hire brand ambassadors to promote good publishing practices and assess new journals’ applications. Nature

- « Previous

- 1

- 2