Switzerland tops in global open access ranking

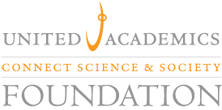

According to the study conducted by the EU, Switzerland ranks first in the global open access ranking. Croatia and Estonia take the 2nd and 3rd position respectively.

In Switzerland, currently, 39% of all publicly and privately funded research publications can be freely accessed on open access platforms. Nonetheless, approximately 50% of Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) funded publications are freely accessible. The target of SNSF is to reach 100% by 2020.

The study conducted by the EU is based on the Scopus database. For the study more than 200,000 papers published in the Switzerland between 2009 and 2016 have been analyzed.

In Switzerland open access publication grew by 10 percentage over the past seven years, the study reveals. Moreover, green open access is the dominant one. Out of the total 39%, 29 % is green. The rest 11% is gold.

Factors such as funders’ mandates, journal policies, researcher attitudes, and costs slowed down the pace of open access growth, according to the study.

Read more

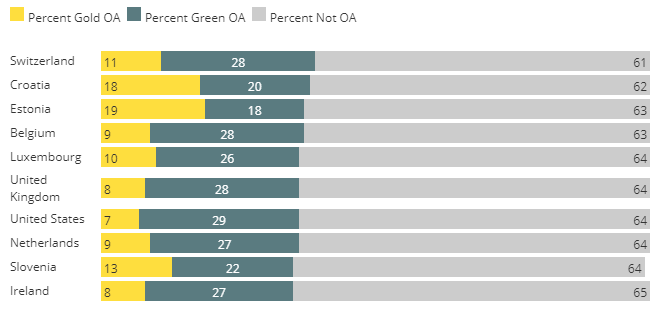

Over the years, open access has shown tremendous growth. The report recently released by OASPA (Open Access Scholarly Publishers Association) affirms this. According to OASPA in 2017 about 219,627 articles were published in fully open access journals. This brings the total number of articles published by the OASPA members, since 2000, to more than 1.2 million. With papers published in hybrid journals this figure is much higher.

Overwhelming majority of the OASPA members publish articles in fully open access journals. However, a significant number of its members also publish articles on hybrid journals, according to the OASPA.

The OASPA Open access publications have shown steady growth over the past years. The most significant growth, nevertheless, was recorded between 2011 and 2012. During this period open access showed 50% growth over the previous years. Nonetheless, the past five-year average open access growth for OASPA members was around 14%. This is still remarkable in several ways.

In 2017, according to OASPA, almost 80% of its members published on five publishers. These are Springer Nature (34%), MDPI (16%), PLOS (11%), Frontiers (9%) and Hindawi (8%).

The OASPA members include publishes such as PLOS, PeerJ, Oxford University Press, Springer Nature, SAGE publications, Cambridge University Press, DOAJ, F1000Research and Knowledge Unlatched. Read more

Initially, it was universities and research institutions in the Netherlands, Germany and French that challenged Elsevier and Springer- the publishing giants. Now, their counterpart in Sweden has taken similar measure. Tomorrow, universities and research institutions in other countries might join. The trend might continue until scientific journals publishing giants fully embrace open access.

The Bibsam consortium, which represents 85 Swedish higher education and research institutions, is convinced that the deal they previously made with Elsevier is not transitioning them to a sustainable open access. They believe that the status quo is not benefiting them. Therefore, they decided not to extend the current deal with Elsevier beyond June 2018.

In 2017 members of the consortium paid Elsevier 13.3 million euros in the form of subscription fees and article processing charges (APCs). Swedish researchers publish around 4,000 articles on Elsevier.

Reference:

Sweden cancels Elsevier contract as open-access dispute spreads

The European Commission’s Horizon2020 research program will phase out by 2020. The commission is working on its successor- Horizon Europe. To make Horizon Europe better, the Commission evaluated Horizon2020 and, according to Science Business, identified six key areas of improvement that the next program should tackle.

First, the EU’s next research program will address issues related to partnership and problems associated with it. This is mainly how institutions and business enter into partnerships to work on research projects. Th commission is also considering to eliminate, Science Business reports, complicated rules that govern partnerships and project acronyms. One issue was how partnerships are formed and maintained. The EU is hopping to form multiple forms of partnerships. First, it encourages public and private organizations to form partnerships. Second, partnership for co-funding. This might be engaging another research funder co-funding research project in partnership with the EU. Third, long term partnership aimed mostly at benefiting big projects.

Second, it will focus on improving research gaps between the East and the West. Usually western European countries get bigger research funding than Eastern countries. Under Horizon 2020, Eastern nations can apply for better funding through teaming, twining and ERA Chairs. Horizon Europe hopes to further improve this.

Third, Europe makes scientific discoveries. Nonetheless, according to Carlos Moedas, it lacks bold innovators. Researchers in the continent are lagging behind in terms of turning innovations into new products, services and processes in the way it impacts markets. The EU, through Horizon Europe, hopes to address this challenge. To make this happen the EU already puts European Innovation Council in place. Accordingly, Horizon Europe will make funding for innovators available through two tracks. The first one is through pathfinder grant for early stage and high-risk innovation projects. This is open for both individuals and companies. The second one is through accelerator funding. Accelerator funding aimed at enabling innovators get products and services to market.

Fourth, Horizon 2020 makes open access publishing mandatory. Nevertheless, compliance rate is not satisfactory- only two-thirds of the researchers comply with the standard. The EU believes that Horizon Europe will address this too. Under the next program open access will be the general rule.

Fifth, the EU acknowledges the importance of international cooperation for research and hopes to realize it via the Horizon Europe program. This makes international participation easy, mostly for research institutions based in developed countries. Access to funding opportunities for entities based in the third countries will be facilitated through a reciprocal means.

Finally, another area where Horizon 2020 did not do well is outreaching citizens. With Horizon Europe the EU hopes to facilities greater outreach to citizens. This is to make science readily understandable by citizens.

What will improve in Horizon Europe? 6 main things, EC draft says

The European Commission has embarked on a series of research programs. Before Horizon2020 it was Framework Program (FP) 7. Then came Horizon2020 (aka FP 8) and now its end is approaching. As a result, the European Commission has been working on the next program (FP 9) that follows it. The name for the next program remained illusive. It seems the EU loved Horizon and the succeeding program might settle with Horizon affixing ‘Europe’ to its ending. That means ‘Horizon Europe’ will be the most likely name for the next program (FP 9).

The name Horizon Europe is not made public yet. It will be made public when the commission will unveil its next program (FP 9) in June, Science Business reported. Read more on Science Business