NASA launches a massive open access archive called SpacePub

NASA’S Dwayne Brown announced most of the agency’s research would be available on a new public access portal called SpacePub. Nasa dropped the news on its official website on August 16. It seems NASA is committing to a new open access era, and publishing almost all of its scientific data online would be a solid first step.

PubSpace is the new public access portal created by the governmental space agency. The website is an open access archive that contains original NASA science articles.

Open Access means anyone can access the data without having to purchase the investigation previously. The data on PubSpace will be available for reading, analysis, and download within one year of publication. So far, the website only has 861 research articles in its database.

The White House is behind the SpacePub

NASA’s new policy was prompted by a request issued by the White House in 2013. The Office of Science and Technology Policy, which directs major science-funding agencies, urged researchers to increase the public access to results of publicly funded research.

Research uploaded at PubSpace will include all type of studies. The available content on the website features studies about exercises routines, maintaining health during long-duration space missions, the prospects for life on Titan, to the risk of miscarriage for flight attendants exposed to cosmic radiation.

NASA will keep consulting the scientific community, publishers, and institutions to maximize the access to research results.

NASA changes its ways to adopt Open Access policies

The agency will change its research policies in 2016. From now on, NASA-funded authors and co-authors are obliged to deposit copies of their peer-reviewed scientific publications and its data on PubSpace. Research regarding patents, personal privacy topics, export control, proprietary restriction, or national security issues will not be undisclosed on the website.

The open access trend on scientific investigations is growing by the day. Due to the high publishers’ prices, researchers are switching to the Internet. Papers are being published directly on the net to avoid the monopoly on most academic publishings. Open access is also said to promote new investigation by giving other scientists a starting point.

SpacePub provides a win-win scenario for both NASA and the users

The website will benefit NASA and its users at the same time. By publishing its papers online for free, the agency encourages scientists and enthusiast on developing them. In other words, the researchers get free data, and the organization gets free “staff.”

“This’ll be the first time that NASA’s had all of their publications in one place, so we estimate what our publication rate is for the agency, but this will actually be able to tell us what it is…And we’ll be able to show even further what we’re doing with taxpayer dollars,” Said NASA’s Deputy Chief Scientist, Gale Allen during an interview with FedScoop’s Samantha Ehlinger.”

The Acceleration of Open Access

Does it seem like a lot is going on all of a sudden, or am I just old and out of touch? (Don’t answer that.)

I noted with loud applause the launch of SocArXiv just in the nick of time. SSRN had been a for-profit but pretty useful place to store papers in the social sciences, but it was fairly old-school; since it didn’t have the resources to make renovations, it teamed up with Elsevier and that makes it no longer useful for those who think making research findings public should be in the public interest, not in shareholders’ interest. While SocArXiv builds out its infrastructure, it’s got a place where you can put your research and good reasons why you should.

One of the reasons Elsevier acquired SSRN was to branch into supporting scientists’ entire workflow, because that’s where the action will be as the ways we share our research evolve. Well, as it turns out, there’s a non-profit that is already doing exactly this, and it’s playing host to SocArXiv. The Center for Open Science has developed a sweet platform – the Open Science Framework – where scholars can put their stuff, creating an open source infrastructure for researchers’ entire workflow. (Yes, you can! Right now! And librarians, we can explore their institutional option.) Other projects of the Center for Open Science include encouraging reproducibility and finding ways to align practices with principles, such as rewarding openness instead of incentivizing publication of research in places that are not public to most working scientists. It’s all pretty ambitious, but it’s exciting to see that people are thinking big thoughts about how to build new structures and practices that help scientists do their work while living up to their better natures. (And if you’re wondering how we got into this mess in the first place, Kevin Smith has just reviewed Catherine Fisks’ Working Knowledge, which helps explain how corporations altered our concept of copyright, authorship, and intellectual property. Yet another book I haven’t read.)

So we have a Center for Open Science building a fantastic platform for storing and sharing and Cold Springs Harbor with its bioRxiv, and MLA, which has built the MLA Commons for its members with a place to share your research and teaching materials, and now, holy smokes, the American Chemical Society, which not too long ago lobbied against open access to federally funded research, is now looking into creating their own preprint server.

And today I discover the Humanities Commons is coming?!? I feel faint. So much going on. So much positive change in the air.

One fascinating aspect of this is trying to figure out how exactly the culture is changing. Librarians found out with their institutional repositories that building it alone doesn’t make them come. Hard work doesn’t necessarily bring on a cultural shift, either; institutional affiliation has less gravitational pull than disciplines and societies. Even within disciplines, it’s hard for projects like bioRxiv and MLA Commons to attract scholars and scientists who feel the systems they are familiar with are good enough, or that making their work open is too risky or too much work. But with so many projects taking off, and with such robust platforms rolling out to challenge whatever the big corporations will have to offer, I’m feeling pretty optimistic about our capacity to align the public value of scholarship with our daily practices – and optimistic about the willingness of rising scholars to change the system.

I may have trouble keeping up with it all, but that’s okay. It’s moving in the right direction. Source InsideHigherEd

Strengthening Research through Data Sharing

Data sharing has incredible potential to strengthen academic research, the practice of medicine, and the integrity of the clinical trial system. Some benefits are obvious: when researchers have access to complete data, they can answer new questions, explore different lines of analysis, and more efficiently conduct large-scale analyses across trials. Other advantages, such as providing a guardrail against conflicts of interest in a clinical trial system in which external sponsorship of research is common and necessary, are less visible yet just as critical.

I appreciate that there are many policy, privacy, and practical issues that need to be addressed in order to make data sharing practical and useful for the research community, but the stakes are too high to step back in the face of that challenge.

One policy proposal that I am particularly enthusiastic about is making data sharing a condition of publication in major medical journals. In a recent letter to the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE), I applauded the committee’s work in developing a framework for data sharing.1 The ICMJE’s proposal would require that, as a condition of having their research manuscripts considered for publication, authors share the deidentified patient data on which their results are based. This requirement would be a significant step forward in improving the transparency of clinical trials for consumers and the academic medical community. Although the privacy of participants must be protected, access to the data underlying trial results can provide an avenue for independent confirmation of results and further analyses of the data set, raising the bar for academic rigor and integrity and speeding the progress of medical research.

As I told the members of the ICMJE, I believe that linking data sharing with publication can also help address the patchwork landscape of current regulations related to the sharing of clinical trial data. Because regulatory agencies have different protocols and requirements for sharing data related to the drugs and devices they approve, access to data about a clinical trial often hinges on which agency handles a regulatory submission rather than on the value of these data to consumers and researchers. By requiring data sharing as a condition of publication, journals can help synchronize and expand existing data-sharing practices.

I am also encouraged by the potential of such proposals to improve compliance with existing laws and regulations related to the reporting of clinical trial results. Each of the several ongoing efforts to increase data sharing through other routes has faced unique challenges. U.S. law has required the posting of summary clinical trial research results to the ClinicalTrials.gov database since the adoption of the Food and Drug Administration Amendment Act (FDAAA) in 2007. However, recent analyses have highlighted variation across sectors when it comes to trial sponsors’ compliance with this law, in part due to a lack of final regulations, which leaves uncertainty about standards and impedes the ability of federal agencies to enforce requirements.2-4 The European Medicines Agency has developed a policy that would require patient-level data to be disclosed after a drug has been approved. This plan has been delayed because of disagreement among stakeholders about how to share these data. Compliance with the more rigorous ICMJE requirements, though it will not automatically harmonize existing regulations, could nonetheless create a baseline expectation that data will be shared and prepare researchers to comply with other mandates.

Requiring researchers to file a data-sharing plan for patient-level data when they initially register a trial could increase pressure on trial sponsors to post results in a timely fashion, regardless of the type of trial, the country of origin of the research, and whether or not the research is being performed to support approval of a new medical product.

The costs associated with preparing data for sharing can and should be built into the grants, cooperative agreements, and contracts that researchers negotiate with trial sponsors; in other words, expenses associated with administering data-sharing protocols must be treated as a standard, necessary aspect of the costs of carrying out a clinical trial. And over the long run, data sharing may help reduce costs by allowing researchers to avoid duplicating trials or to answer questions without undertaking a separate data-collection effort.

Widespread practices of data sharing can also help to address concerns about conflicts of interest that may arise when clinical trials are funded by industry sponsors that stand to profit from favorable research results. By making trial results available for independent scrutiny by outside reviewers, data sharing makes it less likely that trial sponsors can buy the analysis and results they want. Expanding opportunities for scrutiny through data transparency raises the bar for integrity in analysis and interpretation of results, helping to improve the reproducibility and rigor of our clinical trial system.

As the research community and policymakers develop and implement data-sharing requirements, I urge them to craft clear standards for granting qualified researchers access to the data underlying published results in cases in which the data cannot be made public. I recognize that some types of data may necessitate additional protections to preserve the rights and privacy of trial participants and researchers. However, these protections should not place undue burdens on researchers or restrict data access to an overly narrow pool of researchers, nor should they be used to shield data from public view when no legitimate justification exists for restricting public access.

I understand the trepidation that some academics in medical research feel when they contemplate publicly sharing data. As an academic myself, I know the professional stakes attached to credit for original research. I expect that the field will engage in vigorous debate over what length of delay is appropriate before individual-level patient data are released publicly. However, I urge researchers with concerns about academic credit or a new way of doing things not to lose sight of the bigger picture: transparency and reanalysis of data are core practices of rigorous, peer-reviewed research, and increasing access to data will ultimately strengthen — rather than erode — these practices.

Finally, in considering how to encourage data sharing, I urge members of the medical research community to also consider ways to improve the public sharing of information from trials that have produced null, inconclusive, or negative results. As a recent study emphasized, negative trial results have a “sizeable scientific impact,” yet they are less likely to find their way into the pages of major medical journals.5 Encouraging the publication of such trials and the release of their underlying data will help to further accelerate medical progress, uphold the ethical standards of human-subjects research, and help in holding industry sponsors accountable.

Data sharing holds incredible promise for strengthening the practice of medical research and the integrity of our clinical trial system. I look forward to following these proposals as they continue to develop and urging their implementation. Source NEJM

For many years, within the scientific and publishing arena, the journal impact factors (JIFs) has been the most commonly used and referred to approach of research output impact (quality) measurement approach. This approach which focuses on journal quality measurement has many flows, research indicates.

Though it is still widely used, the journal impact factor has come under increasing scrutiny. The main argument here is that JIF does not necessarily reflect the impact or quality of article published in a given journal, argues VéroniqueKiermer. The research conducted by team of researchers from Université de Montréal, Imperial College London, PLOS, eLife, EMBO Journal, The Royal Society, Nature and Science, posted on BioRxiv underscores that ‘article cannot be judged on the basis of the impact factor of the journal on which it is published.’ This is due to that fact that most articles published in high impact factor journals do not exhibit high impact level- mostly measured through article citation. The research found out that there are articles published in low impact factor journals and with a high impact factor; mostly measured though article citation. Conversely, there are many articles published in a high impact factor journals that make very little impact.

Despite its weaknesses the JIF remained the most widely used tool to evaluate scientists. This is mainly attributed to culture, convenience, and lack of proper alternatives. ‘The misuse of the Impact Factor has become institutionalized,’ argues Véronique Kiermer.

The status quo is not sustainable. There is increasing awareness among the scholarly community about need for a change. The call for a shift from heavily relying on journals impact factor (which by itself a reflection of citation count) to accommodating diverse and reliable techniques to measure research quality and its impacts is gaining momentum. Among stakeholders consensus is building around superiority of Article Level Metrics (which measures individual articles impact) over the JIF as a barometer of research output quality and impact. This might usher new era of measuring articles quality based on every articles merit (ALM) not on the JIF.

According to Véronique Kiermer no single metric accurately reflects impact of different research output. That is the reason why measuring articles social media impact (share, like etc.) and download are becoming import impact measuring factors. Development of articles tracking technologies, through DOI (digital object identifier), has made this possible.

Scholars are pushing for multiple research quality measurement approaches. It seems that some publishers, researchers and research funders are responding to it; surely not at a desired speed. This signals publishers’ and scholars’ gradual move towards fully embracing robust and reliable research quality measurement techniques.

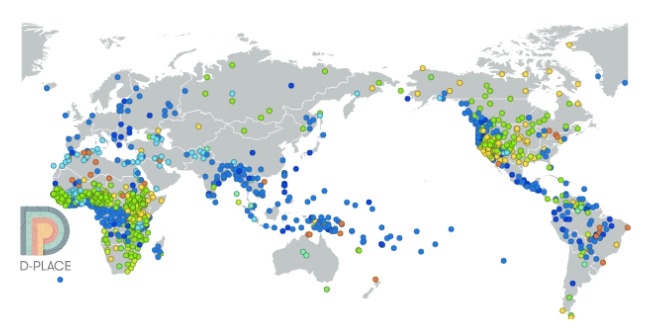

D-PLACE — the Database of Places, Language, Culture and Environment — is an expandable, open access database that brings together a dispersed body of information on the language, geography, culture and environment of more than 1,400 human societies. It comprises information mainly on pre-industrial societies that were described by ethnographers in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The team’s paper on D-PLACE is published in the journal PLOS ONE.

“Human cultural diversity is expressed in numerous ways: from the foods we eat and the houses we build, to our religious practices and political organization, to who we marry and the types of games we teach our children,” said Kathryn Kirby, a postdoctoral fellow in the Departments of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology and Geography at the University of Toronto and lead author of the study. “Cultural practices vary across space and time, but the factors and processes that drive cultural change and shape patterns of diversity remain largely unknown.

“D-PLACE will enable a whole new generation of scholars to answer these long-standing questions about the forces that have shaped human cultural diversity.”

Co-author Fiona Jordan, senior lecturer in anthropology at the University of Bristol and one of the project leads said, “Comparative research is critical for understanding the processes behind cultural diversity. Over a century of anthropological research around the globe has given us a rich resource for understanding the diversity of humanity — but bringing different resources and datasets together has been a huge challenge in the past.

“We’ve drawn on the emerging big data sets from ecology, and combined these with cultural and linguistic data so researchers can visualize diversity at a glance, and download data to analyze in their own projects.”

D-PLACE allows users to search by cultural practice (e.g., monogamy vs. polygamy), environmental variable (e.g. elevation, mean annual temperature), language family (e.g. Indo-European, Austronesian), or region (e.g. Siberia). The search results can be displayed on a map, a language tree or in a table, and can also be downloaded for further analysis.

It aims to enable researchers to investigate the extent to which patterns in cultural diversity are shaped by different forces, including shared history, demographics, migration/diffusion, cultural innovations, and environmental and ecological conditions.

D-PLACE was developed by an international team of scientists interested in cross-cultural research. It includes researchers from Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human history in Jena Germany, University of Auckland, Colorado State University, University of Toronto, University of Bristol, Yale, Human Relations Area Files, Washington University in Saint Louis, University of Michigan, American Museum of Natural History, and City University of New York.

The diverse team included: linguists; anthropologists; biogeographers; data scientists; ethnobiologists; and evolutionary ecologists, who employ a variety of research methods including field-based primary data collection; compilation of cross-cultural data sources; and analyses of existing cross-cultural datasets.

“The team’s diversity is reflected in D-PLACE, which is designed to appeal to a broad user base,” said Kirby. “Envisioned users range from members of the public world-wide interested in comparing their cultural practices with those of other groups, to cross-cultural researchers interested in pushing the boundaries of existing research into the drivers of cultural change.” Source UToronto